# The Neuroscience of Free Will

Molecular biologists have assured neuroscientists for years that the molecular structures involved in neurons are too large to be affected significantly by quantum phenomena.

They know that while most biological structures are remarkably stable, and thus apparently determined, quantum effects drive the mutations that provide variation in the gene pool. So our question is how the typical structures of the brain have evolved to deal with microscopic, atomic level, noise. Can they ignore it because they are adequately determined large objects, or might they have remained sensitive to the noise?

We can expect that if quantum noise, or even ordinary thermal noise, offered beneficial advantages, there would have been evolutionary pressure to take advantage of noise.

Proof that our sensory organs have evolved until they are working at or near quantum limits is evidenced by the eye's ability to detect a single photon (a quantum of light energy), and the nose's ability to smell a single molecule.

Biology provides many examples of ergodic creative processes following a trial and error model. They harness chance as a possibility generator, followed by an adequately determined selection mechanism with implicit information-value criteria. Whether such randomness plays a role in the mind has been challenged. For decades, neuroscientists have looked to the experiments of Benjamin Libet to prove that the brain contains a deterministic mechanism that makes a decision long before the human being is conscious of the decision.

## Libet Experiments

The neurologist [Benjamin Libet](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/scientists/libet/) performed a sequence of remarkable experiments in the early 1980's that were enthusiastically, if mistakenly, adopted by determinists and compatibilists to show that human free will does not exist.

His measurements of the time before a subject is aware of self-initiated actions have had a enormous, mostly negative, impact on the case for human free will, despite Libet's view that his work does nothing to deny human freedom.

Since free will is best understood as a complex idea combining two antagonistic concepts - freedom and determination, ["free" and "will,"](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/free_will.html) in a temporal sequence, Libet's work on the timing of events can also be interpreted as supporting our "[two-stage model](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/two-stage_models.html)" of free will.

Indeed, Libet himself argued that there was still room for a veto over a decision that may have been made unconsciously over 300 milliseconds before the agent is consciously aware of the decision to flex a finger, but before the action of muscles flexing. In his 2004 book, _Mind Time: The Temporal Factor in Consciousness_, he presented a diagram of his work.

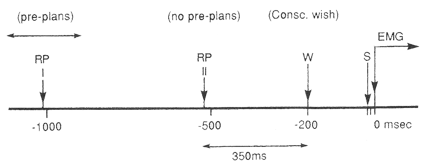

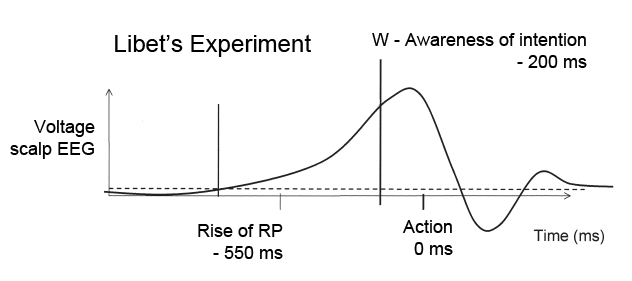

> Fig. 4.3. Diagram of sequence of events, cerebral (RPs) and subjective (W), that precede a self-initiated voluntary act.

>

> Relative to "0" time (muscle activation), cerebral RPs begin first, either with preplanned acts (RP I) or with no preplannings (RP II). Subjective experience of earliest awareness of the wish to move (W) appears at about -200 msec; this is well before the act ("0" time) but is some 350 msec after even RP II. Subjective timings of the skin stimulus (S) averaged about —50 msec, before the actual stimulus delivery time.

Libet says the diagram shows room for a "conscious veto."

> The finding that the volitional process is initiated unconsciously leads to the question: Is there then any role for conscious will in the performance of a voluntary act (Libet, 1985)? The conscious will (W) does appear 150 msec before the motor act, even though it follows the onset of the cerebral action (1W) by at least 400 msec. That allows it, potentially, to affect or control the final outcome of the volitional process. An interval msec before a muscle is activated is the time for the primary motor cortex to activate the spinal motor nerve cells, and through them, the muscles. During this final 50 msec, the act goes to completion with no possibility of its being stopped by the rest of the cerebral cortex.)

>

> The conscious will could decide to allow the volitional process to go to completion, resulting in the motor act itself. Or, the conscious will could block or "veto" the process, so that no motor act occurs.

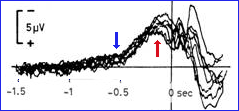

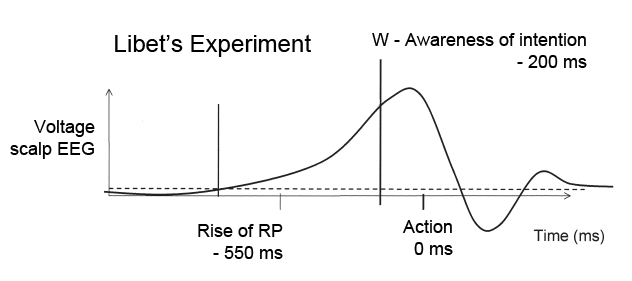

The original discovery that an electrical potential (of just a few microvolts - μV) is visible in the brain long before the subject flexes a finger was made by Kornhuber and Deecke (1964). They called it a "_Bereitschaftspotential_" or readiness potential.

As shown on Kornhuber's RP diagram, the rise in the readiness potential was clearly visible at about 550 milliseconds before the flex of the wrist (blue arrow).

The neurobiologist [John Eccles](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/scientists/eccles/) speculated that the subject must become conscious of the _intention_ to act before the onset of this readiness potential. Libet had the idea that he should test Eccles's prediction.

[

Libet's clock. Click to enlarge image.

](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/scientists/libet/clock.html "Libet's clock.Click to enlarge image")

Libet's 1983 experiments measured the time when the subject became consciously aware of the decision to move the finger. Libet created a dot on the screen of an oscilloscope circulating like the hand of a clock, but more rapidly. The subject was asked to note the position of the moving dot when he/she was aware of the conscious decision to move a finger or wrist.

Libet found that although conscious awareness of the decision preceded the subject's finger motion by only 200 milliseconds, the rise in the Type II readiness potential was clearly visible at about 550 milliseconds before the flex of the wrist. The subject showed _unconscious_ activity to flex about 350 milliseconds before reporting _conscious_ awareness of the decision to flex (the red arrow above). Indeed an earlier slow and very slight rise in the readiness potential can be seen as early as 1.5 seconds before the action.

Libet's results were eagerly adopted by the deniers of free will to indicate that the mind had been made up unconsciously, long before any awareness of "conscious will."

Psychologist [Daniel Wegner](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/scientists/wegner/) thinks that conscious will may be just an _epiphenomenon_, something that is caused by brain events, not the cause of such events. As he put it in his 2002 book _The Illusion of Conscious Will_,

> We don't know what specific unconscious mental processes the RP might represent....The position of conscious will in the time line suggests perhaps that the experience of will is a link in a causal chain leading to action, but in fact it might not even be that. It might just be a loose end — one of those things, like the action, that is caused by prior brain and mental events.

>

> (_The Illusion of Conscious Will_, MIT Press, p.55)

>

> Does the compass steer the ship? In some sense, you could say that it does, because the pilot makes reference to the compass in determining whether adjustments should be made to the ship's course. If it looks as though the ship is headed west into the rocky shore, a calamity can be avoided with a turn north into the harbor. But, of course, the compass does not steer the ship in any physical sense. The needle is just gliding around in the compass housing, doing no actual steering at all. It is thus tempting to relegate the little magnetic pointer to the class of epiphenomena — things that don't really matter in determining where the ship will go.

>

> Conscious will is the mind's compass. As we have seen, the experience of consciously willing action occurs as the result of an interpretive system, a course-sensing mechanism that examines the relations between our thoughts and actions and responds with "I willed this" when the two correspond appropriately. This experience thus serves as a kind of compass, alerting the conscious mind when actions occur that are likely to be the result of one's own agency. The experience of will is therefore an indicator, one of those gauges on the control panel to which we refer as we steer. Like a compass reading, the feeling of doing tells us something about the operation of the ship. But also like a compass reading, this information must be understood as a conscious experience, a candidate for the dreaded "epiphenomenon" label.

>

> (_The Illusion of Conscious Will_, MIT Press, p.317)

[Bernard Baars](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/scientists/baars/) says there are two important time scales of consciousness

> Sensory events occurring within a tenth of a second merge into a single conscious sensory experience, suggesting a 100-millisecond scale. But working memory, the domain in which we talk to ourselves or use our visual imagination, stretches out over roughly 10-second steps. The tenth-of-a-second level is automatic, while the 10-second level is shaped by conscious plans and goals.

>

> (_In the Theater of Consciousness_, p.48)

The kinds of deliberative and evaluative processes that are important for [free will](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/) involve longer time periods than those studied by Benjamin Libet.

Note also that the abrupt and rapid decisions to flex a finger measured by Libet bear little resemblance to the kinds of [two-stage](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/two-stage_models.html) deliberate decisions for which we can first [freely generate alternative possibilities for action](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/possibilities.html), then evaluate which is the best of these possibilities in the light of our reasons, motives, and desires - [first "free," then "will."](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/cogito/)

We can correlate the beginnings of the readiness potential (350ms before Libet's conscious will time "W" appears) with the early stage of the two-stage model, when alternative possibilities are being generated, in part at random. The early stage may be delegated to the subconscious, which is capable of considering multiple alternatives ([William James](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/philosophers/james/)' "blooming, buzzing confusion") that would congest the single stream of consciousness.

[Alfred Mele](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/philosophers/mele/), in his 2009 book _Effective Intentions, the Power of Conscious Will_, criticized the interpretation of the Libet results on two grounds. First, the mere appearance of the RP a half-second or more before the action in no way makes the RP the _cause_ of the action. It may simply mark the beginning of forming an _intention_ to act. In our two-stage model, it is the considering of possible options.

Libet himself argued that there is enough time after the W moment (a window of opportunity) to _veto_ the action, but Mele's second criticism points out that such examples of "free won't" would not be captured in Libet experiments, because the recording device is triggered by the action (typically flicking the wrist) itself.

Thus, although all Libet experiments ended with the wrist flicking, we are not justified in assuming that the rise of the RP (well before the moment of conscious will) is a _cause_ of the wrist flicking. Libet knew that there were very likely other times when the RP rose, but which did not lead to a flick of the wrist.