# The Self, Spirit, Soul, or _Psyche_

Celebrating [René Descartes](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/philosophers/descartes/), the first _modern_ philosopher, and his famous phrase _Ego cogito, ergo sum_, we call our model for mind the [Ego](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/mind/ego/).

Our [two-stage model](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/two-stage_models.html) for free will we call the [Cogito](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/cogito/). Our model for an _objective_ [value](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/value/) in the universe, independent of humanity, we call [_Ergo_](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/value/ergo/). And our model for the totality of human knowledge we call the [_Sum_](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/knowledge/sum/).

The Ego is more or less synonymous with the Self, the Soul, or the Spirit - [Gilbert Ryle](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/philosophers/ryle/)'s "ghost in the machine." We see it as _immaterial_ [information](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/introduction/information/). An immaterial self with [causal](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/causality.html) power is almost universally denied by modern philosophers as _[metaphysical](http://metaphysicist.com/)_, along with related ideas such as [consciousness](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/problems/consciousness/) and [libertarian or indeterministic free will](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/).

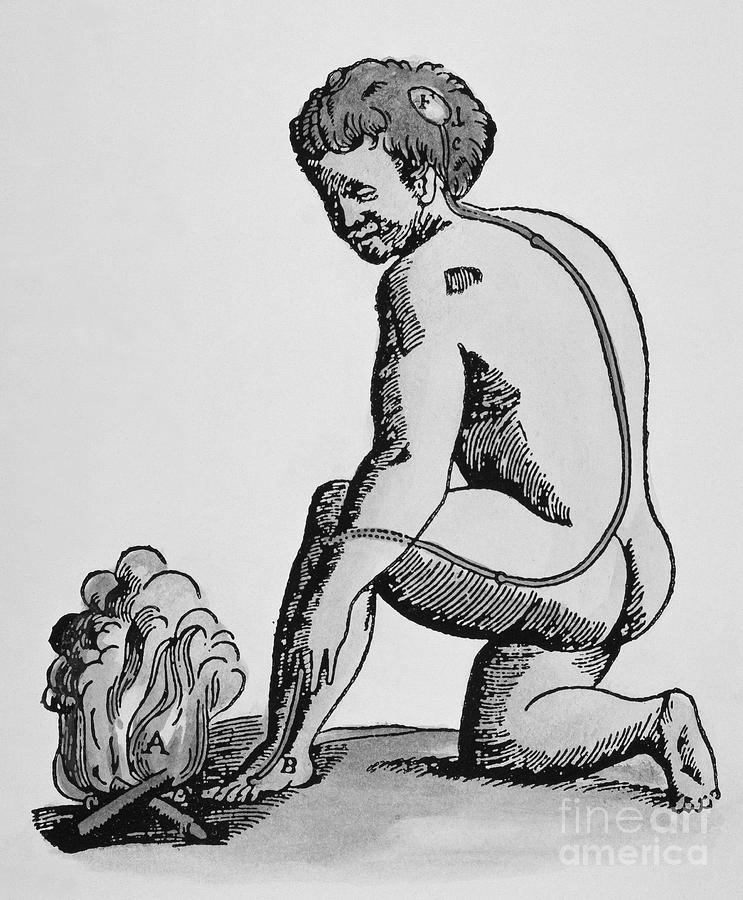

Descartes' illustration of the reflex path from a foot feeling pain from a fire (A), up a nerve to a gland in the mind and back down to pull back the foot (B).

It is important to note that Descartes made the mind both _immaterial_ and the locus of [undetermined](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/indeterminism.html) [freedom](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/). For him, the body is a [deterministic](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/determinism.html) mechanical system of tiny fibres causing movements in the brain (the afferent sensations), which then can pull on other fibres to activate the muscles (the efferent nerve impulses). This is the basis of stimulus and response theory in modern physiology (reflexology). It is also the basis behind _connectionist_ theories of mind. An appropriate neural network (with all the necessary logical connections) need only connect the afferent to the efferent signals. Descartes thought no thinking mind is needed for animals.

Descartes' suggestion that animals are machines included the notion that man too is _in part_ a machine - the human body obeys deterministic causal laws. But for Descartes man also has a soul or spirit that is exempt from determinism and thus from what is known today as "[">causal closure](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/causality.html)." But how, we must ask, can the mind both cause something physical to happen and yet itself be [acausal](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/causa_sui.html), exempt from causal chains?

Our Thoughts Are Free, Our Actions Are Willed, Self-Determined,

Limited Only by Our Creative Control Over Matter and Energy

Most simply, it derives from the discovery by information philosophy that our thoughts are [indeterministic](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/indeterminism.html) and [free](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/), whereas our actions are [adequately determined](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/adequate-determinism.html) by our will. This combination of ideas is the basis for our [two-stage model](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/cogito/) of free will and [self-determination](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/self-determination.html).

The "self" or ego, the psyche or spirit or soul, is the self of this self-determination. Self-determination is of course limited by our ability to control matter and energy, but within those physical constraints our selves can act and can take [responsibility](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/responsibility.html) for our actions.

The Self is often identified with one's "character." This is the basis for saying that our choices and decisions are made by evaluating the [alternative possibilities](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/possibilities.html) in accordance with our reasons, motives, feelings, desires, etc. These are in turn often the consequence of our past experiences, along with inherited (biologically built-in) preferences. And this bundle of motivating factors is essentially what is known as our character. Someone familiar with all of our preferences would be able to predict our actions with some certainty, though not perfectly, when faced with particular options and the circumstances. The self is the [agent](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/mind/agent/) that is [responsible](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/freedom/responsibility.html) for those actions.

The self is also often described as the seat of [consciousness](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/problems/consciousness/). Information philosophy defines consciousness as awareness of and attention to information coming in to the mind and the resulting actions that are responsive to the external stimuli (or to bodily proprioceptions). Consciousness thus depends in part on past experiences which are recalled by the [Experience Recorder and Reproducer (ERR)](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/knowledge/ERR/) as responses to external stimuli. In this way, "_what it's like to be_" a conscious agent depends on the kinds of experiences that the agent has had in the past and whose resemblances to present experience provide contextual meaning.

[David Hume](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/philosophers/hume/)'s so-called "bundle theory" of the self is quite consistent with the information philosophy view. His fundamental ideas of causality, contiguity, and resemblance as the basis for the association of ideas are essential aspects of the [Experience Recorder and Reproducer](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/knowledge/ERR/). He said,

> It is plain, that in the course of our thinking, and in the constant revolution of our ideas, our imagination runs easily from one idea to any other that resembles it, and that this quality alone is to the fancy a sufficient bond and association. It is likewise evident that as the senses, in changing their objects, are necessitated to change them regularly, and take them as they lie contiguous to each other, the imagination must by long custom acquire the same method of thinking, and run along the parts of space and time in conceiving its objects.

>

> > (_A Treatise of Human Nature_. 4.1, 2)

The frog's eye famously filters out some visual events (moving concave images) while triggering strong reactions to others, like sticking out a tongue to capture moving convex objects. _What it's like to be_ a frog depends then on those experiences that are recorded and thus meaningful to the frog. Hume might say the perception has no resemblance to anything in the mind of the frog. The frog's self is therefore not conscious of those sensations that are filtered out of its perceptions.

## The Problem of Other Minds

The problem of other minds is often posed as just one more problem in [epistemology](https://www.informationphilosopher.com/knowledge/), that is, how can be certain about the existence of other minds, since I can't be certain about anything in the external world. But can also be seen as a problem about meaningful communications and agreement about shared concepts in two minds. This makes information philosophy an excellent tool for approaching the classic problem.

For some philosophers, the problem of other minds is dis-solved by denying the existence of the mind in general - as merely an epiphenomenon with no causal powers. Other philosophers identify the problem with Hume's claim that when he looked inside he saw no self. Our positing the self as the immaterial information about stored past experiences clearly helps here.

Still others admit that they have perceptions and sensations, but how could they possibly know what another person is experiencing. For example, I know when I feel pain, but I don't know what is really happening in another person who looks to be feeling pain.

The standard answer here is that other persons seem in most respect to be similar to myself, and so by analogy their experiences must be similar to mine. This analogical inference is weak because of its literal superficiality, because we don't get an inside view of the other mind.

For information philosophy, the problem of knowledge can solved by identifying partial isomorphisms in external information structures with the pure information in a mind. This suggests the solution of other minds. Looked at this way, the problem of other minds is easier to solve than the general epistemological problem. The general problem must compare different things, the pure information of mental ideas with the information abstracted from a concrete external information structure. The problem of other minds compares similar things (concepts).

When, by interpersonal communications, we compare the pure information content in two different minds, we are reaching directly into the other mind in its innermost _immaterial_ nature. To be sure, we have not felt the same sensations nor had identical experiences. We have not "felt the other's pain." But we can plant ideas in the other mind, and then watch it alter the other person's actions in a way totally identical to what that information, that knowledge, has been used for in our own actions.

This establishes the existence, behind the external bodily (material) behaviors of the other person, of the same _immaterial_, metaphysical mind model, the same theory of mind, in the other mind, as the one in our own.